100 Years Ago Today: Woodrow Wilson’s Cathedral Burial

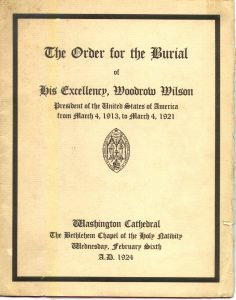

One hundred years ago today, on Feb. 6, 1924, President Woodrow Wilson was buried at the Cathedral – the first and so far only U.S. president to be buried in Washington, D.C.

There’s a lot to say about Wilson, the nation’s 28th president (1913-1921). In the decades following his death, he was lionized as an idealistic peacemaker who led the nation through World War I; many saw him as the architect of the idea democratic nations must protect democracy through strength and shared security.

More recently, he has come under intense scrutiny for his domestic legacy, particularly his record on race. On his watch, the federal workforce was segregated and Black civil servants were demoted and pushed aside. He hosted a screening of the virulently racist film “The Birth of a Nation” in the White House, and took questionable measures on civil liberties and espionage in the name of national security.

1924 Burial

First Lady Edith Wilson chose the Cathedral as her husband’s final resting place for several reasons (although it was not the first site she considered). She felt he had done his most important work in the nation’s capital, and her image of her husband matched the Cathedral’s ambitions to be a place where the heroes of democracy could be celebrated and commemorated.

President Wilson’s 15-minute funeral was held at his house near Dupont Circle, and he was originally interred in a subterranean vault beneath Bethlehem Chapel. Later, a cenotaph was erected in the chapel that attracted thousands of visitors.

His body was moved upstairs to the nave in 1956, the centennial of his birth. The slab from the cenotaph — featuring a cross-shaped crusader’s sword with a rounded tip to symbolize peace — moved with him to his new tomb. The ornate bay is decorated with symbols of his career, his wartime presidency and his long record in academia. Above, a stained-glass window depicts peace as given by God, destroyed by man and restored through Jesus Christ.

2024 Legacy

Needless to say, his legacy is … complicated.

Historians can (and have) spin themselves into circles debating what he did, didn’t do, and why. Much of his iconic status was carefully curated by Edith Wilson, who was interred in the Cathedral crypt in 1961. His prominent placement in the Cathedral was also managed by his grandson, the Very Rev. Francis Sayre, Jr., who was born in the White House and later was the Cathedral’s longest-serving dean.

Historians can (and have) spin themselves into circles debating what he did, didn’t do, and why. Much of his iconic status was carefully curated by Edith Wilson, who was interred in the Cathedral crypt in 1961. His prominent placement in the Cathedral was also managed by his grandson, the Very Rev. Francis Sayre, Jr., who was born in the White House and later was the Cathedral’s longest-serving dean.

We’ll leave the historical and political legacy to the historians. Here at the Cathedral, we approach it from a slightly different angle.

As Christians who come from the Anglican tradition, we cling to the idea of the Via Media, or middle way. In a world that demands strict adherence to black or white, we flourish in the gray, the messy middle, where we acknowledge that we are both sinner and saint, wonderfully made and yet deeply broken, capable of great good and tempted by great evil. As our Canon Theologian, Kelly Brown Douglas, puts it, “We are a people of the cross, where the evil in our humanity meets the love that we call God. That’s where we need to live, in the messy complex realities where God comes to meet us.”

In that light, we consider Wilson (and every other person in this Cathedral) in that both/and category — neither villain nor visionary, but perhaps a bit of both. Lionizing our historical figures amounts to cheap grace. Dismissing them and demonizing them shows very little grace at all.

Woodrow Wilson, like every human, is a complex and contradictory figure. He was an advocate for peace and a progressive visionary, but he embraced segregation and turned a blind eye to racial violence. His legacy challenges each of us to examine our own motivations and actions; we make no excuse for President Wilson’s racist beliefs, actions or inactions.

Every person depicted and memorialized in the Cathedral – save one, Jesus Christ – is a sinner in need of God’s redemptive grace, and Woodrow Wilson is no different.

A century after President Wilson’s body was laid to rest at the Cathedral, our challenge as Americans is to redouble our efforts, in our own time, to racial equity and reconciliation. The complex legacy of each historical figure within the Cathedral is an invitation to deep reflection and self-examination about what each of us can do to advance God’s beloved community.