Women’s History Month: Why It Matters to Bring Women to the Center

What happens when subjugated voices come to the center of historical understanding?

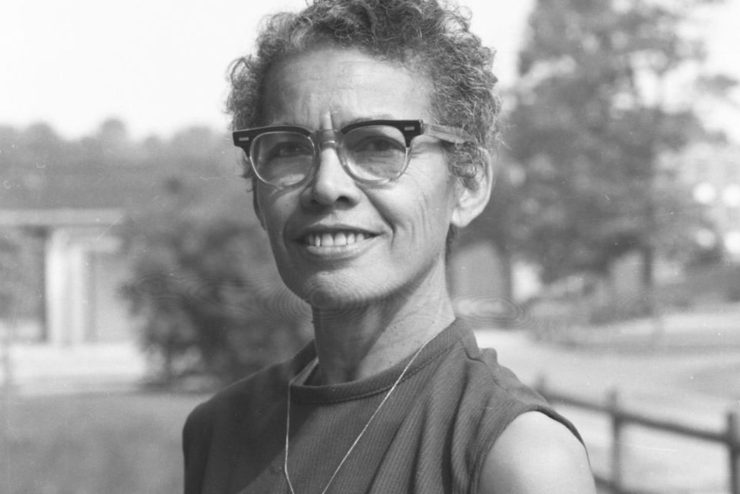

Anna Julia Cooper, the 19th century scholar, educator and activist, answers that question for us in her 1892 book, “A Voice from the South by a Black Woman of the South.” Dr. Cooper says, “only the BLACK WOMAN can say when and where I enter, in the quiet, undisputed dignity of my womanhood, without violence and without suing or special patronage, then and there the whole Negro race enters with me.”

Cooper was an Episcopal laywoman from Washington, D.C., and was only the fourth Black woman in America to earn a Ph.D. Scholars will tell you she was one of the first who fully articulated a sense of Black feminist thought, and she argued that Black women have a unique vantage point from which to understand the complex realities of injustice. And because of that, they’re especially equipped to help us cast a unique moral vision for enacting justice.

Because of their race, gender and frequently their class, Black women have a unique perspective on oppression. Dr. Cooper makes clear that when we can bring their often subjugated voices to the center of our history, we can all move a little bit closer to the just future that God promises us all.

In other words, when we listen to the voices who have been victims of injustice, it helps us know what justice looks like.

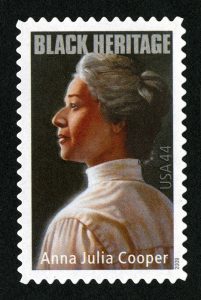

What Anna Julia Cooper articulated, Pauli Murray demonstrated in her work as lawyer, activist and priest.

Murray was the first Black female priest ordained in the Episcopal Church — I was among the first 10 — and she was often ahead of her time. She was fighting against separate-but-equal well before Rosa Parks and Thurgood Marshall, and arguing for equal treatment for women in the courts years ahead of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. More recently, Murray has emerged as an icon for the gender non-conforming community. Not until the last few years has America begun to understand how much of an unsung trail-blazer she was.

Read more: First Black Female Episcopal Priest Joins U.S. Currency

Watch the Trailer: “My Name is Pauli Murray” (Amazon Prime Video)

New York Times: Pauli Murray Should Be a Household Name: A New Film Shows Why.

Because of her history, she knew what it would take to create a world that reflected “True community . . . based upon equality, mutuality and reciprocity . . . . one that ‘affirms the richness of individual diversity as well as the common human ties that bind us together.’”

Murray envisioned a world where people would be able to walk in freedom “proudly before God and humanity glorifying [their unique] self-expression.” Committed to making such a world possible, Murray refused to accept a segregated society. Murray believed that such a society not only betrays our “common human ties” but also fosters internal segregated realities for persons like her.

That’s why Murray fought, as an activist and lawyer, for civil rights, labor rights and women’s rights. That work was Murray’s form of ministry; it was how she partnered with God to foster a future where all enjoyed freedom and justice.

It was no wonder, therefore, that Murray’s journey culminated in ordination, here at the Cathedral in 1977. Murray explained that it was with ordination, that “all of the strands of my life came together. Descendent of slaver and of slave owner, I had already been called poet, lawyer, teacher, and friend. Now I was empowered to minister the sacrament of One in whom there is no north or south, no black or white, no male or female—only the spirit of love and reconciliation drawing us all toward the goal of human wholeness.”

So what happens when subjugated voices come to the center, whether during Women’s History Month or the whole year round?

When subjugated voices like Anna Julia Cooper’s and Pauli Murray’s come to the center of our historical knowing, that’s when we can foster a world that truly promotes human wholeness. When and where these voices enter, the whole human race enters with them.